A practitioner-oriented overview based on the Local Government Code of 1991 (LGC) and leading jurisprudence

1. Statutory Framework

| Source |

Key Provisions |

| Constitution (Art. X, §5) |

LGUs may create their own sources of revenue. |

| LGC 1991 (R.A. 7160), Book II, Title II |

§§197-283 govern the levy, collection, and enforcement of local taxes, including RPT. |

| Implementing Rules & Regulations (IRR) of the LGC |

Part IV, Rule XXX |

| Supreme Court cases |

FELS Energy v. Province of Batangas (G.R. F-729), City of Makati v. Tagaytay Highlands (G.R. 222263, 2021) etc., interpret LGU powers and taxpayer defenses. |

2. When and How the Tax Becomes Due

| Event |

Timing |

Notes |

| Accrual |

1 January every year (LGC §232) |

Tax attaches to the land, building, and machinery that exist on that date. |

| Basic tax & SEF tax |

Payable on or before 31 January or in four equal quarterly installments (31 Mar, 30 Jun, 30 Sep) (§250) |

Some provinces/cities adopt incentives for advance payment. |

| Special levies (e.g., idle land, benefit assessments) |

Billed and collected together with the basic tax unless an ordinance fixes another schedule. |

|

3. Administrative Penalties for Late or Non-Payment

- Interest (LGC §255)

- 2 % of the unpaid amount per month of delay.

- Capped at 36 months (i.e., maximum 72 %).

- Interest runs separately for each installment.

- Tax Delinquency (§256)

- Occurs the day immediately after a quarterly due date lapses.

- Entire year’s balance may be declared delinquent once any installment is missed.

- Notice of Delinquency (§258)

- Local treasurer must:

- Post at the main LGU building and in the barangay, and

- Publish once a week for two consecutive weeks in a newspaper of general circulation.

- Notice must state the date of auction sale (not less than 30 days after posting).

- Warrant of Levy (§260)

- May be issued 30 days after delinquency.

- Annotated on the title at the Registry of Deeds; constitutes a statutory lien that is superior to mortgages and other encumbrances (except constitutional tax-exemptions).

- Advertisement and Public Auction (§§261-263)

- Sale advertised for 30 days.

- Highest bidder wins; if no bidder, LGU may purchase the property ipso jure (§264).

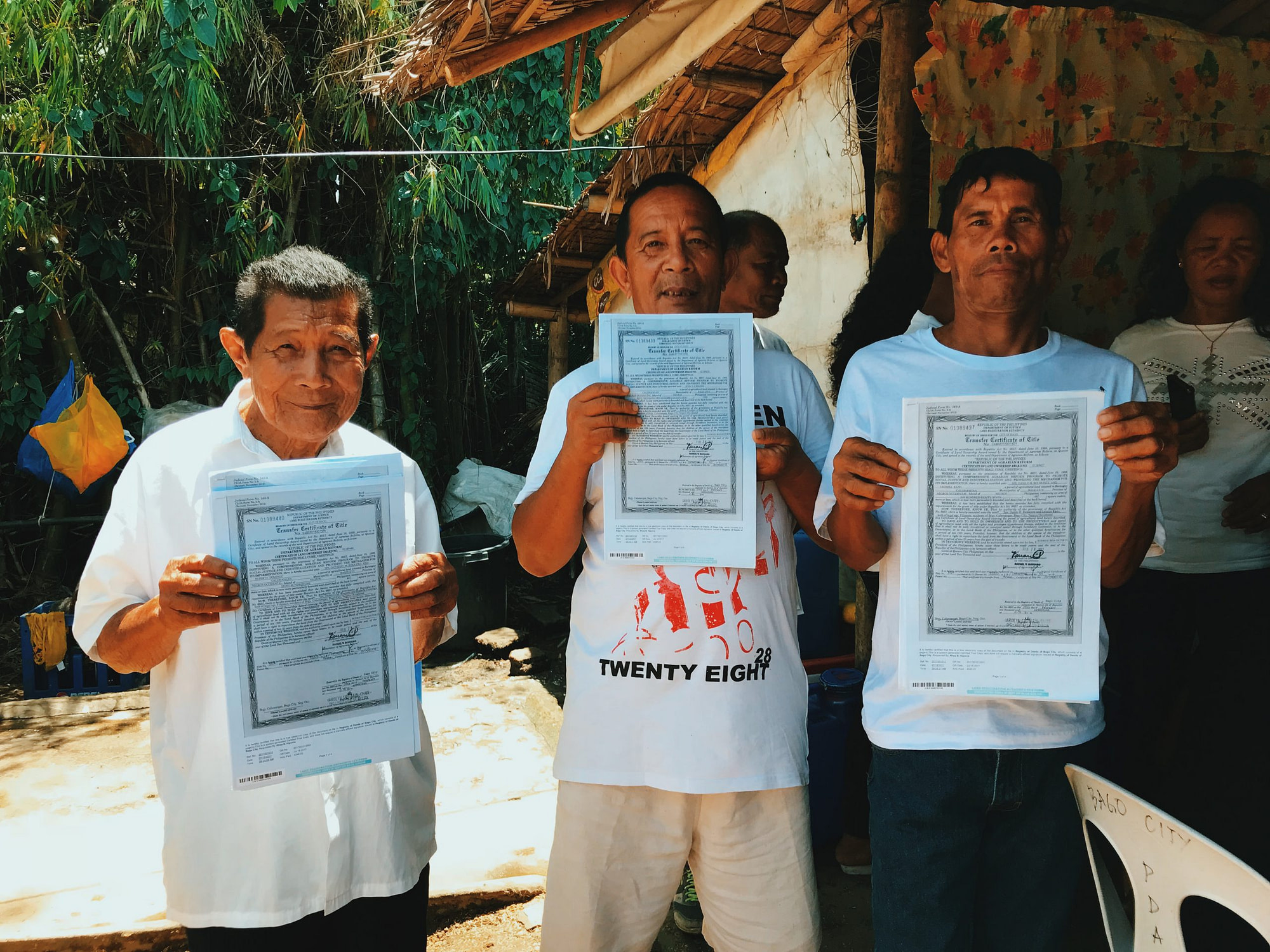

- A Certificate of Sale is issued and annotated on the title.

- Redemption Period (§262)

- Owner or any interested party may redeem within one (1) year from the date of sale by paying:

- The delinquent tax,

- Interest up to the date of sale, plus

- Interest on the purchase price at up to 2 % per month.

- Upon redemption, the certificate of sale is cancelled and a certificate of redemption is issued.

- Final Deed Conveying Title (§263)

- If not redeemed within one year, the treasurer executes a Final Deed to the Purchaser, free from the lien of taxes and earlier encumbrances.

- The owner forfeits all rights to the property except a share in any surplus of the sale proceeds (rare, since taxes and costs usually consume the price).

- Possessory Rights & Ejectment

- The purchaser may take possession after the redemption period.

- Courts have upheld ejectment suits anchored on a final deed executed under §263.

4. Ancillary Civil and Commercial Consequences

| Consequence |

Practical Effect |

| Blocking of Land Registration Transactions |

Registry of Deeds requires a Real-Property Tax Clearance Certificate for transfers, mortgages, subdivision/consolidation plans, and issuance of condominium CCTs. |

| Cloud on Title / Lower Market Value |

The levy and certificate of sale are annotated, discouraging buyers and lenders. |

| Difficulty Renewing Business Permits |

Cities and municipalities require RPT clearance for an establishment’s annual business-permit renewal. |

| Ineligibility for Government Incentives |

Some BOI/PEZA or tourism incentives require proof of local-tax compliance. |

| Impact on Estate Settlement |

Heirs cannot obtain an electronic Certificate Authorizing Registration (e-CAR) from the BIR without RPT clearance. |

5. Criminal Liability?

Non-payment per se is a civil breach, not a criminal offense.

- However, §274 punishes local officials who fail to perform collection duties.

- Tax evasion under the NIRC does not apply to local taxes.

- A taxpayer who knowingly falsifies documents to secure a tax clearance may incur liability under the Revised Penal Code (falsification/estafa).

6. Taxpayer Remedies and Mitigating Measures

| Remedy |

Statutory Basis |

Key Points |

| Installment/Partial Payments |

§250 |

Interest computed only on the unpaid portion. |

| Protest (Before payment) |

§252 |

Must be filed within 30 days from notice of assessment; decision due 60 days; appealable to the LBAA. |

| Appeal to LBAA, CBAA, CTA, SC |

§§226-231 |

Can question legality of assessment, but not the collection procedure once tax is delinquent. |

| Amnesty/Condonation |

§276; special laws (e.g., R.A. 11213, the 2019 estate-tax amnesty) |

Sangguniang Panlalawigan/Panglungsod may condone interest in cases of calamity, crop failure, or special public interest. |

| Compromise/Abatement |

Similar to BIR compromise; LGU may accept partial settlement subject to sanggunian approval. |

|

| Judicial Injunction |

Rare; courts generally require payment under protest before entertaining suits (tax-collection is the lifeblood of government doctrine). |

|

7. Enforcement Hierarchy vis-à-vis Personal Property

For local business taxes and fees the treasurer may distrain personal property before levying realty (§175).

For RPT, levy on realty is the primary—and exclusive—administrative remedy. Personal property cannot be distrained to satisfy RPT.

8. Priority of Liens

- National Taxes (e.g., estate or donor’s tax)

- Real-Property Tax Lien – “superior to all liens, charges, or encumbrances” (§257)

- Mortgage Liens / Usufruct / Easements

- Subsequent Attachments / Judgments

Thus, a mortgagee’s foreclosure sale is subordinate to prior RPT liens; the buyer at foreclosure must settle delinquent RPT or risk levy.

9. Special Rules for Special Classes of Property

| Property |

Notes on Enforcement |

| Government-owned but patrimonial property |

Subject to levy; doctrine in City of Lapu-Lapu v. PEA (2017). |

| Tax-exempt entities (charities, non-stock / non-profit schools) |

Exempt from basic RPT but the SEF and other special levies may still apply (C.B. Garayblas v. SSS, 2016). |

| Machinery |

May be a separate subject of levy; if machinery is removed or dismantled, the tax lien follows the parts unless paid (IRR Rule IV). |

10. Effect of LGU Non-Compliance with Due-Process Steps

Failure to strictly comply with §258 posting + publication or §260 warrant formalities voids the levy and subsequent sale (Heirs of Malate v. Gamboa, G.R. 181409, 2013).

- Nonetheless, the underlying tax remains due; the treasurer may re-levy within the 5-year prescriptive period (§270) or 10 years if fraud is involved.

11. Prescription

| Action |

Period |

Interruption |

| Assessment/Collection by LGU |

5 years from date tax became due; fraud/falsity extends to 10 years (§270). |

Running is tolled by: (a) service of warrant, (b) taxpayer request for reinvestigation, (c) any court action. |

| Refund by Taxpayer |

2 years from date of payment (§253). |

|

12. Comparative Glance at Condonation Programs (Past Decade)

| Year |

Issuing Authority |

Coverage |

Highlights |

| 2013 |

R.A. 10158 |

Abolished RPT on machineries of independent power producers (IPPs) in energy privatization; national govt assumes liability. |

|

| 2022 |

Various LGUs post-Typhoon Odette |

Provincial boards (Bohol, Southern Leyte, etc.) condoned surcharges and interest for affected barangays. |

|

| 2023 |

Quezon City Ord. SP-3180 |

100 % condonation of interest for delinquencies paid in full within the amnesty window. |

|

13. Practical Tips for Owners, Buyers, and Lenders

- Always secure an updated “Statement of Account” (SOA) from the city/municipal treasurer before closing any real-estate deal.

- Pay in January if cash flow allows—many cities grant a 10 %-20 % discount for advance/full-year payment.

- Monitor quarterly dues using the LGU’s online portal or mobile pay apps (GCash, PayMaya) now accepted in most highly urbanized cities.

- For developers, allocate sufficient escrow for RPT during the project’s pre-selling phase; unpaid RPT can derail subdivision/condo registration.

- For lenders, routinely check Tax Declaration and Real-Property Tax Clearance before loan releases and during annual credit review.

- If already delinquent, explore LGU settlement plans or amnesties—interest condonation can save up to 72 % of the outstanding balance.

14. Key Take-Aways

- The RPT lien is automatic, paramount, and difficult to defeat; ignoring it can literally cost you land.

- Interest alone can double the liability in three years.

- Due-process defects can nullify the levy but not the tax—the LGU can start the process anew.

- Redemption is a strict one-year period; after that, title and possession pass irrevocably.

- Awareness of local amnesty ordinances and timely installment payments are the taxpayer’s best defenses.

Disclaimer: This article synthesizes statutory text, administrative regulations, and Supreme Court decisions current to 26 April 2025. It is not a substitute for formal legal advice. Always confirm any LGU-specific ordinance or amnesty in force at the time of inquiry.