Buying a property is a life-long dream for many people in the Philippines, but it involves a considerable amount of money- the reason why many home-buyers/investors are so careful in transacting with just anybody. That is why the government ensures that the real estate profession is well regulated here in the Philippines, and that the people who introduce themselves are real estate professionals are licensed (like architects, lawyers, doctors, engineers, etc.). This is the primary objective of the Real Estate Service Act of the Philippines, more commonly known as the “RESA Law”.

What is RESA law?

Republic Act No. 9646 or the Real Estate Service Act of the Philippines, which is more commonly referred to as the RESA laws the law that protects the rights of those who call themselves as real estate professionals. This said law took effect on July 30, 2009 and it deals primarily with the acts considered to be real estate services, the penalties corresponding to violations of its provisions and the qualifications of those who may practice the profession. Furthermore, the law is meant to prevent the practice of “colorum” agents and also property sellers who are still patronizing to the so-called freelance illegal property agents to avoid paying taxes and proper commission rates.

Before the RESA Law was introduced in 2009, all real estate brokers were licensed under the Department of Trade and Industry (DTI). When the law was passed, the role of regulating the profession was handed to the Professional Regulation Commission (PRC). However, those already licensed under the DTI are still eligible to get a license from the PRC without taking the Real Estate Broker Licensure Examination (under the so-called grandfather clause).

What can be considered as “engaging in the practice of real estate service”?

Based on Section 27 of the RESA Law, acts constituting the practice of real estate service are as follows:

“Any single act or transaction embraced within the provisions of Section 3(g), Rule II hereof, as performed by real estate service practitioners, shall constitute an act of engaging in the practice of real estate service.”

” Furthermore, Section 3(g) states that:

“g. “Real estate service practitioners” shall refer to and consist of the following: (1) Real estate consultant – a duly registered and licensed natural person who, for a professional fee, compensation or other valuable consideration, offers or renders professional advice and judgment on: (i) the acquisition, enhancement, preservation, utilization or disposition of lands or improvements thereon; and (ii) the conception, planning, management and development of real estate projects.

(2) Real estate appraiser – a duly registered and licensed natural person who, for a professional fee, compensation or other valuable consideration, performs or renders, or offers to perform services in estimating and arriving at an opinion of or acts as an expert on real estate values, such services of which shall be finally rendered by the preparation of the report in acceptable written form.

(3) Real estate assessor — a duly registered and licensed natural person who works in a local government unit and performs appraisal and assessment of real properties, including plants, equipment, and machineries, essentially for taxation purposes.

(4) Real estate broker – a duly registered and licensed natural person who, for a professional fee, commission or other valuable consideration, acts as an agent of a party in a real estate transaction to offer, advertise, solicit, list, promote, mediate, negotiate or effect the meeting of the minds on the sale, purchase, exchange, mortgage, lease or joint venture, or other similar transactions on real estate or any interest therein

(5) Real estate salesperson – a duly accredited natural person who performs service for, and in behalf of a real estate broker who is registered and licensed by the Professional Regulatory Board of Real Estate Service for or in expectation of a share in the commission, professional fee, compensation or other valuable consideration.”

Who are exempted from the RESA Law?

Section 28 of the RESA law stipulates who are exempted from the said law:

- Owners of real property are not required to have a license in order to sell their own property. However, real estate developers are not included because they are regulated by the Housing and Land Use Regulatory Board (HLURB).

- Trustees in bankruptcy or insolvency proceedings.

- People who act pursuant to court orders and duly constituted attorneys that are authorized to negotiate the sale, mortgage, lease, or exchange of real estate.

- Public officers who performs such acts in line with their official duties. Except that government assessors should have a license.

What is prohibited?

Let me quote Section 29 of the RESA Law below:

“SEC. 29. Prohibition Against the Unauthorized Practice of Real Estate Service. No person shall practice or offer to practice real estate service in the Philippines or offer himself/herself as real estate service practitioner, or use the title, word, letter, figure or any sign tending to convey the impression that one is a real estate service practitioner, or advertise or indicate in any manner whatsoever that one is qualified to practice the profession, or be appointed as real property appraiser or assessor in any national government entity or local government unit, unless he/she has satisfactorily passed the licensure examination given by the Board, except as otherwise provided in R.A. No. 9646 and the IRR is a holder of a valid certificate of registration and professional identification card or a valid special/temporary permit duly issued to him/her by the Board and the Commission; and, in the case of real estate brokers and private appraisers, they have paid the required bond as provided for in R.A. No. 9646.”

What are the penalties for violating RA 9646?

Section 39 stipulates that licensed real estate professionals who are proven guilty of violating of the said law, shall be penalized with a fine of not less than Php100, 000.00 or imprisonment of not less than two (2) years. However, if the offender happens to be unlicensed, the penalty shall be double (that would mean Php200, 000.00 or imprisonment of not less than four (4) years.

“For richer, for poorer, in sickness or in health, to love and to cherish till death do us part.” This is part of the marriage vow being recited during weddings. Being married to someone entails not only sharing one’s life but also one’s property with the other. Hence, it is very important to know the liabilities of the common properties of the spouses. Oftentimes, one of the spouses contracts a loan and the common property will sometimes be held responsible in case the contracting spouse defaults in his obligation. The liability of the common property will depend on the type of transaction and other factors provided by law.

In the absence of a marriage settlement or prenuptial agreement, the provisions of the Family Code will apply with regard to the property regime of the spouses. If the marriage was contracted before the Family Code (before 03 August 1988), then the conjugal partnership of gains (CPG) will govern. However, if the marriage was contracted after 03 August 1988, then the absolute community of property (ACP) will apply. For this article, the author will discuss the ACP and its liabilities since the discussion on the CPG will be the subject of another article.

Under the regime of ACP, all property owned by the spouses at the time of the celebration of the marriage or acquired thereafter shall form part of the community property. However, property acquired during the marriage by gratuitous title, as well as the fruits and income thereof; property for exclusive or personal use of each spouse (except jewelry); and property acquired before the marriage by either spouse who has legitimate descendants by a former marriage, as well as the fruits or income thereof, are excluded from the community property.

Anent the liability of the community property, Article 94 of The Family Code states that the ACP shall be liable for the following:

- 1. The support of the spouses, their common children, and legitimate children of either spouse; however, the support of illegitimate children shall be governed by the provisions of the Family Code on Support;

- 2. All debts and obligations contracted during the marriage by the designated administrator-spouse for the benefit of the community, or by both spouses, or by one spouse with the consent of the other;

- 3. Debts and obligations contracted by either spouse without the consent of the other to the extent that the family may have been benefited;

- 4. All taxes, liens, charges and expenses, including major or minor repairs, upon the community property;

- 5. All taxes and expenses for mere preservation made during marriage upon the separate property of either spouse used by the family;

- 6. Expenses to enable either spouse to commence or complete a professional or vocational course, or other activity for self-improvement;

- 7. Ante-nuptial debts of either spouse insofar as they have redounded to the benefit of the family;

- 8. The value of what is donated or promised by both spouses in favor of their common legitimate children for the exclusive purpose of commencing or completing a professional or vocational course or other activity for self-improvement;

- 9. Ante-nuptial debts of either spouse other than those falling under paragraph (7) of this Article, the support of illegitimate children of either spouse, and liabilities incurred by either spouse by reason of a crime or a quasi-delict, in case of absence or insufficiency of the exclusive property of the debtor-spouse, the payment of which shall be considered as advances to be deducted from the share of the debtor-spouse upon liquidation of the community; and

- 10. Expenses of litigation between the spouses unless the suit is found to be groundles

- The question frequently asked is the liability of the other spouse in case the contracting spouse sells the common property. It would depend if the other spouse had knowledge and consent of the transaction. If the husband sold the property without the consent and knowledge of the wife, then the sale is void. However, the transaction shall be considered as a continuing offer and may be perfected upon acceptance of the other spouse. On the other hand, if the husband sold the community property with the knowledge but without the consent of the wife, the contract is merely annullable. The wife has 5 years from the date of the contract to go to court and seek the annulment of the contract.

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/propertytax.asp_edit-4091e7e47aa84fa6b7ea8e49018a08c9.jpg)

Property tax is a charge levied by a government for real estate or tangible personal property.

What Is Property Tax?

A property tax is an annual or semiannual charge levied by a local government and paid by the owners of real estate within its jurisdiction. Property tax is an ad-valorem tax, meaning the amount owed is a percentage of the assessed value of the real estate.

Property tax receipts are the main source of revenue for most local governments in the U.S. They are used to fund schools, police and fire departments, road construction and repairs, libraries, water and sewer departments, and other local services that benefit the community.

In common usage, property tax refers to a tax on immovable possessions like structures or land. Some local jurisdictions also assess property taxes on moveable property such as vehicles and industrial equipment.

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/propertytax.asp-Final-768e8c036b94413591376e5baa43dbb9.png)

Understanding Property Taxes

Property taxes are paid by individuals or legal entities, such as corporations, that own real estate. A tax is assessed on an individual’s primary residence, second home, rental property, and any other real estate they may own, such as a commercial property. Property tax is not assessed to renters.

It is characterized as a regressive tax. That is, the same rate of taxation is applied regardless of the taxpayer’s income. This means the tax burden falls disproportionately on lower-income taxpayers.12

The tax is usually based on the value of the owned property, including land and structures. Many jurisdictions also tax tangible personal property, such as cars and boats. Property tax rates and the types of properties taxed vary by jurisdiction.

Property Tax vs. Real Estate Tax

People often use the terms property tax and real estate tax interchangeably. In fact, not all property taxes are real estate taxes.

Many jurisdictions also levy property taxes against tangible personal property. According to a report by the Tax Foundation, 43 states tax tangible personal property.7

Both types of property can be deducted from federal taxes. However, since the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act of 2017, the deduction has been capped at $10,000 per year for married couples and single taxpayers.8

So here’s the difference: Real estate taxes are taxes on real property only, while property taxes can include both real property and tangible personal property.

What is Land Management

Are you curious about land management? Wondering what exactly it entails and why it’s so important? Look no further. In this article, we’ll provide an in-depth overview of land management and its significance in various contexts. Land management refers to the active process of controlling and overseeing the use, development, and conservation of land and its natural resources. This practice encompasses a range of activities, including land use planning, environmental planning, forestry, agriculture, and more. It aims to strike a balance between economic development and environmental sustainability, ensuring that land resources are utilized responsibly and efficiently. Effective land management is crucial for maintaining biodiversity, combating climate change, and promoting sustainable development. From preserving natural habitats to facilitating urban growth, land management plays a vital role in shaping our landscapes and ensuring their long-term viability. Whether you’re an environmental enthusiast or simply curious about how land is managed, this article will provide valuable insights into the world of land management. So, let’s dive in and explore this fascinating topic further.

Importance of Land Management

Land management is the bedrock upon which societies build their futures. It is a critical element of how we coexist with the natural world and how we shape the environment in which future generations will live. From the food we eat to the spaces where our children play, the principles of land management affect every aspect of our lives.

The importance of land management cannot be overstressed. It is the means by which we can reconcile the often competing demands of agriculture, housing, industry, and conservation. Without effective land management, these areas could easily fall into conflict, resulting in the depletion of natural resources, loss of biodiversity, and irreversible environmental damage.

Moreover, land management is pivotal for disaster risk reduction. It helps in the planning of settlements away from vulnerable areas, the conservation of water catchments, and the management of land use to reduce the incidence and impact of floods, landslides, and other natural disasters. It is a critical component in safeguarding human life and property against the unpredictable forces of nature.

The Role of Land Management in Sustainable Development

The United Nations’ Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) have put a spotlight on the significance of managing our land resources sustainably. Land management practices are central to achieving many of these goals, particularly those related to ending poverty, ensuring food security, and fostering resilience to climate change.

Sustainable land management is about integrating land, water, biodiversity, and environmental management to meet human needs while ensuring the long-term sustainability of ecosystem services. It is about finding a middle ground where economic development can proceed without stripping the Earth of its ability to support us in the future.

Effective land management contributes to sustainable development by promoting land use that supports productive activities, such as agriculture and forestry, while conserving soil and water resources. It helps to maintain the health of ecosystems, which in turn supports the livelihoods of billions of people worldwide, especially those living in rural areas.

Key Principles of Land Management

The principles of land management serve as a compass guiding the multitude of decisions that must be made about how land is used and conserved. These principles are shaped by a combination of scientific knowledge, policy frameworks, and societal values.

One fundamental principle is the idea of stewardship – that we are caretakers of the land, responsible not only for its health today but for its vitality for future generations. This long-term perspective is essential in ensuring that land management practices do not sacrifice the future for short-term gains.

Another principle is the concept of integrated management, which recognises that land is part of a larger ecosystem. Land management decisions must consider the interaction between land, water, and living resources to promote a holistic approach to sustainability.

Additionally, the principle of participation is crucial. Inclusive land management that involves local communities, indigenous peoples, and a range of stakeholders leads to more effective and equitable outcomes. It ensures that the needs and rights of all are considered in the decision-making process.

ypes of Land Management Practices

Land management practices vary widely, depending on the objectives and the context. However, they can generally be grouped into several categories, each with its own set of techniques and approaches.

In agriculture, sustainable land management practices include crop rotation, contour farming, agroforestry, and the use of organic fertilisers. These practices are aimed at improving soil fertility and water retention, reducing erosion, and enhancing crop yields.

In urban areas, land management practices involve careful planning of land use to accommodate residential, commercial, and industrial needs while preserving green spaces and public amenities. This includes zoning laws, urban design, and the creation of parks and conservation areas within cities.

Forestry practices include sustainable logging, reforestation, and the management of forests for multiple uses, such as recreation, wildlife habitat, and water protection. These practices aim to ensure that forest resources can be used without compromising their health and diversity.

Challenges in Land Management

Land management is fraught with challenges that stem from a variety of sources. One major challenge is the conflict between different land uses and the interests of various stakeholders. Balancing the needs of agriculture, industry, conservation, and residential development requires careful negotiation and often leads to difficult compromises.

Another challenge is the issue of land degradation, which is exacerbated by practices such as overgrazing, deforestation, and the overuse of chemical fertilisers and pesticides. These practices can lead to soil erosion, loss of fertility, and pollution, making it harder to use the land sustainably in the future.

Climate change presents an additional layer of difficulty for land managers. As weather patterns become more unpredictable and extreme events more common, managing land resources in a way that promotes resilience and adaptation becomes increasingly complex.

Tools and Technologies for Effective Land Management

To meet the challenges of land management, professionals are turning to a range of tools and technologies. Geographic Information Systems (GIS) have become indispensable, allowing land managers to map and analyse land use patterns, environmental data, and other critical information.

Remote sensing technology, including satellite imagery and drones, provides detailed and up-to-date information about land cover, vegetation health, and changes in land use over time. This technology is crucial for monitoring deforestation, urban expansion, and the effects of natural disasters.

Computer modelling is another tool that is used extensively in land management. Models can simulate the impacts of different land use scenarios, helping decision-makers to predict the outcomes of their choices and plan more effectively for sustainable development.

Land Management Strategies for Different Ecosystems

Each ecosystem requires a tailored approach to land management, reflecting its unique characteristics and the needs of the people who rely on it. In arid and semi-arid regions, land management strategies focus on water conservation and the prevention of desertification.

In tropical rainforests, strategies aim to balance the economic benefits of logging with the need to preserve biodiversity and protect the rights of indigenous communities. This often involves sustainable forestry practices and the establishment of protected areas.

In wetlands, land management strategies are centred around water quality and flood control. Wetlands are critical for the health of watersheds, and their management often involves restoring degraded areas and creating buffer zones to protect them from pollution and development.

Land Management and Climate Change

Climate change is both a challenge to and a focus of contemporary land management. Land managers must now consider the carbon sequestration capacity of forests, peatlands, and other ecosystems in their planning. This is because these land types play a crucial role in mitigating the effects of climate change by absorbing carbon dioxide from the atmosphere.

Adaptive land management strategies are also being developed to cope with the impacts of climate change. These strategies include the creation of wildlife corridors to allow species to migrate in response to shifting habitats and the implementation of more resilient agricultural practices.

Furthermore, land managers are increasingly involved in climate change mitigation efforts. This involves promoting land use practices that reduce greenhouse gas emissions, such as the protection of existing forests and the restoration of degraded lands.

Learning Objectives

- Be familiar with the various kinds of interest in real property.

- Know the ways that two or more people can own property together.

- Understand the effect of marriage, divorce, and death on various forms of property ownership.

Overview

The transfer of property begins with the buyer’s selection of a form of ownership. Our emphasis here is not on what is being acquired (the type of property interest) but on how the property is owned.

One form of ownership of real property is legally quite simple, although lawyers refer to it with a complicated-sounding name. This is ownership by one individual, known as ownership in severalty. In purchasing real estate, however, buyers frequently complicate matters by grouping together—because of marriage, close friendship, or simply in order to finance the purchase more easily

When purchasers group together for investment purposes, they often use various forms of organization—corporations, partnerships, limited partnerships, joint ventures, and business trusts. The most popular of these forms of organization for owning real estate is the limited partnership. A real estate limited partnership is designed to allow investors to take substantial deductions that offset current income from the partnership and other similar investments, while at the same time protecting the investor from personal liability if the venture fails.

But you do not have to form a limited partnership or other type of business in order to acquire property with others; many other forms are available for personal or investment purposes. To these we now turn.

Joint Tenancy

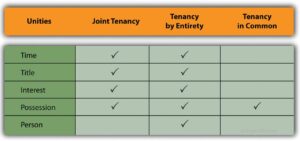

Joint tenancy is an estate in land owned by two or more persons. It is distinguished chiefly by the right of survivorship. If two people own land as joint tenants, then either becomes the sole owner when the other dies. For land to be owned jointly, four unities must coexist:

- Unity of time. The interests of the joint owners must begin at the same time.

- Unity of title. The joint tenants must acquire their title in the same conveyance—that is, the same will or deed.

- Unity of interest. Each owner must have the same interest in the property; for example, one may not hold a life estate and the other the remainder interest.

- Unity of possession. All parties must have an equal right to possession of the property (see Figure 12.1 “Forms of Ownership and Unities”).

Figure 12.1 Forms of Ownership and Unities

Suppose a woman owns some property and upon marriage wishes to own it jointly with her husband. She deeds it to herself and her husband “as joint tenants and not tenants in common.” Strictly speaking, the common law would deny that the resulting form of ownership was joint because the unities of title and time were missing. The wife owned the property first and originally acquired title under a different conveyance. But the modern view in most states is that an owner may convey directly to herself and another in order to create a joint estate.

When one or more of the unities is destroyed, however, the joint tenancy lapses. Fritz and Gary own a farm as joint tenants. Fritz decides to sell his interest to Jesse (or, because Fritz has gone bankrupt, the sheriff auctions off his interest at a foreclosure sale). Jesse and Gary would hold as tenants in common and not as joint tenants. Suppose Fritz had made out his will, leaving his interest in the farm to Reuben. On Fritz’s death, would the unities be destroyed, leaving Gary and Reuben as tenants in common? No, because Gary, as joint tenant, would own the entire farm on Fritz’s death, leaving nothing behind for Reuben to inherit.

Tenancy by the Entirety

About half the states permit husbands and wives to hold property as tenants by the entirety. This form of ownership is similar to joint tenancy, except that it is restricted to husbands and wives. This is sometimes described as the unity of person. In most of the states permitting tenancy by the entirety, acquisition by husband and wife of property as joint tenants automatically becomes a tenancy by the entirety. The fundamental importance of tenancy by the entirety is that neither spouse individually can terminate it; only a joint decision to do so will be effective. One spouse alone cannot sell or lease an interest in such property without consent of the other, and in many states a creditor of one spouse cannot seize the individual’s separate interest in the property, because the interest is indivisible.

Tenancy in Common

Two or more people can hold property as tenants in common when the unity of possession is present, that is, when each is entitled to occupy the property. None of the other unities—of time, title, or interest—is necessary, though their existence does not impair the common ownership. Note that the tenants in common do not own a specific portion of the real estate; each has an undivided share in the whole, and each is entitled to occupy the whole estate. One tenant in common may sell, lease, or mortgage his undivided interest. When a tenant in common dies, his interest in the property passes to his heirs, not to the surviving tenants in common.

Because tenancy in common does not require a unity of interest, it has become a popular form of “mingling,” by which unrelated people pool their resources to purchase a home. If they were joint tenants, each would be entitled to an equal share in the home, regardless of how much each contributed, and the survivor would become sole owner when the other owner dies. But with a tenancy-in-common arrangement, each can own a share in proportion to the amount invested.

Community Property

In ten states—Alaska, Arizona, California, Idaho, Louisiana, Nevada, New Mexico, Texas, Washington, and Wisconsin—property acquired during a marriage is said to be community property. There are differences among these states, but the general theory is that with certain exceptions, each spouse has an undivided equal interest in property acquired while the husband and wife are married to each other. The major exception is for property acquired by gift or inheritance during the marriage. (By definition, property owned by either spouse before the marriage is not community property.) Property acquired by gift of inheritance or owned before the marriage is known as separate property. Community property states recognize other forms of ownership; specifically, husbands and wives may hold property as joint tenants, permitting the survivor to own the whole.

The consequence of community property laws is that either the husband or the wife may manage the community property, borrow against it, and dispose of community personal property. Community real estate may only be sold or encumbered by both jointly. Each spouse may bequeath only half the community property in his or her will. In the absence of a will, the one-half property interest will pass in accordance with the laws of intestate succession. If the couple divorces, the states generally provide for an equal or near-equal division of the community property, although a few permit the court in its discretion to divide in a different proportion.

Condominiums

In popular parlance, a condominium is a kind of apartment building, but that is not its technical legal meaning. Condominium is a form of ownership, not a form of structure, and it can even apply to space—for example, to parking spaces in a garage. The word condominium means joint ownership or control, and it has long been used whenever land has been particularly scarce or expensive. Condominiums were popular in ancient Rome (especially near the Forum) and in the walled cities of medieval Europe.

In its modern usage, condominium refers to a form of housing involving two elements of ownership. The first is the living space itself, which may be held in common, in joint tenancy, or in any other form of ownership. The second is the common space in the building, including the roof, land under the structure, hallways, swimming pool, and the like. The common space is held by all purchasers as tenants in common. The living space may not be sold apart from the interest in the common space.

Two documents are necessary in a condominium sale—the master deed and the bylaws. The master deed (1) describes the condominium units, the common areas, and any restrictions that apply to them; (2) establishes the unit owner’s interest in the common area, his number of votes at owners’ association meetings, and his share of maintenance and operating expenses (sometimes unit owners have equal shares, and sometimes their share is determined by computing the ratio of living area or market price or original price of a single unit to the whole); and (3) creates a board of directors to administer the affairs of the whole condominium. The bylaws usually establish the owners’ association, set out voting procedures, list the powers and duties of the officers, and state the obligations of the owners for the use of the units and the common areas.

Cooperatives

Another popular form of owning living quarters with common areas is the cooperative. Unlike the person who lives in a condominium, the tenant of a cooperative does not own a particular unit. Instead, he owns a share of the entire building. Since the building is usually owned by a corporation (a cooperative corporation, hence the name), this means that the tenant owns stock in the corporation. A tenant occupies a unit under a lease from the corporation. Together, the lease and stock in the building corporation are considered personal, not real, property.

In a condominium, an owner of a unit who defaults in paying monthly mortgage bills can face foreclosure on the unit, but neighbors in the building suffer no direct financial impact, except that the defaulter probably has not paid monthly maintenance charges either. In a cooperative, however, a tenant who fails to pay monthly charges can jeopardize the entire building, because the mortgage is on the building as a whole; consequently, the others will be required to make good the payments or face foreclosure.

Time-Shares

A time-share is an arrangement by which several people can own the same property while being entitled to occupy the premises exclusively at different times on a recurring basis. In the typical vacation property, each owner has the exclusive right to use the apartment unit or cottage for a specified period of time each year—for example, Mr. and Mrs. Smith may have possession from December 15 through December 22, Mr. and Mrs. Jones from December 23 through December 30, and so on. The property is usually owned as a condominium but need not be. The sharers may own the property in fee simple, hold a joint lease, or even belong to a vacation club that sells time in the unit.

Time-share resorts have become popular in recent years. But the lure of big money has brought unscrupulous contractors and salespersons into the market. Sales practices can be unusually coercive, and as a result, most states have sets of laws specifically to regulate time-share sales. Almost all states provide a cooling-off period, or rescission period; these periods vary from state to state and provide a window where buyers can change their minds without forfeiting payments or deposits already made.

Key Takeaway

Property is sometimes owned by one person or one entity, but more often two or more persons will share in the ownership. Various forms of joint ownership are possible, including joint tenancies, tenancy by the entirety, and tenancy in common. Married persons should be aware of whether the state they live in is a community property state; if it is, the spouse will take some interest in any property acquired during the marriage. Beyond traditional landholdings, modern real estate ownership may include interests in condominiums, cooperatives, or time-shares.

Exercises

- Miguel and Maria Ramirez own property in Albuquerque, New Mexico, as tenants by the entirety. Miguel is a named defendant in a lawsuit that alleges defamation, and an award is made for $245,000 against Miguel. The property he owns with Maria is worth $320,000 and is owned free of any mortgage interest. To what extent can the successful plaintiff recover damages by forcing a sale of the property?

- Miguel and Maria Ramirez own property in Albuquerque, New Mexico, as tenants by the entirety. They divorce. At the time of the divorce, there are no new deeds signed or recorded. Are they now tenants in common or joint tenants?

In general, only Filipino citizens and corporations or partnerships with least 60% of the shares are owned by Filipinos are entitled to own or acquire land in the Philippines. Foreigners or non-Philippine nationals may, however, purchase condominiums, buildings, and enter into a long-term land lease.

InCorp Philippines assists foreigners, expatriates/expats, former Filipino nationals, OFWs, Balikbayans, and corporations purchasing and acquiring real property in the Philippines and can provide relevant information on Philippine laws and regulations regarding property purchase and acquisition, reviewal of general contracts, asset protection contracts, deeds of sale, taxes, and entire estate planning. In addition, we can introduce you to local real estate brokers to assist you in finding the type of property you are looking for in the Philippines.

Can a Foreigner Own Land in the Philippines?

Ownership of land in the Philippines is highly-regulated and reserved for persons or entities legally defined as Philippine nationals or Filipino citizens. For this purpose, a corporation with 60% Filipino ownership is treated as a Philippine national.

Foreigners or expats interested in acquiring land or real property through aggressive ownership structures must consider the provisions of the Philippines’ Anti-Dummy Law to determine how to proceed. A major restriction in the law is the restriction on the number of foreign members on the Board of Directors of a landholding company (which is limited to 40% foreign participation). Another concern is the possible forfeiture of the property if the provisions of the law is breached.

Are there any exceptions to the restriction on foreign land acquisition?

Yes, there are. The list of exceptions to the restriction are as follows:

- Acquisition before the 1935 Constitution

- Acquisition through hereditary succession if the foreigner is a legal or natural heir

- Purchase of not more than 40% interest in a condominium project

- Purchase by a former natural-born Filipino citizen subject to the limitations prescribed by law (natural-born Filipinos who acquired foreign citizenship is entitled to own up to 5,000 sq.m. of residential land, and 1 hectare of agricultural or farm land).

- Filipinos who are married to aliens and able to retain their Filipino citizenship (unless by their act or omission they have renounced their Filipino citizenship)

Can a Corporation Own Land in the Philippines?

Foreign nationals, expats or corporations may completely own a condominium or townhouse in the Philippines. To take ownership of a private land, residential house and lot, and commercial building and lot, they may set up a domestic corporation in the Philippines. This means that the corporation owning the land has less than or up to 40% foreign equity and is formed by 5-15 natural persons of legal age as incorporators, the majority of which must be Philippine residents.

Can a Foreigner Lease Real Estate Property in the Philippines?

Leasing land in the Philippines on a long-term basis is an option for foreigners, expats or foreign corporations with more than 40% foreign equity. Under the Investors’ Lease Act of the Philippines, they may enter into a lease agreement with Filipino landowners for an initial period of up to 50 years renewable once for an additional 25 years.

Can a Foreigner Own Residential Houses or Buildings in the Philippines?

Foreign ownership of a residential house or building in the Philippines is legal as long as the foreigner or expat does not own the land on which the house was built.

Can a Foreigner Own Condominiums or Townhouses in the Philippines?

The Condominium Act of the Philippines (RA 4726) expressly allows foreigners to acquire condominium units and shares in condominium corporations up to 40% of the total and outstanding capital stock of a Filipino-owned or controlled condominium corporation.

However, there are a very few single-detached homes or townhouses in the Philippines with condominium titles. Most condominiums are high-rise buildings.

Can a Foreigner Married to a Filipino Citizen Hold a Land Title in the Philippines?

If holding a title as an individual, a typical situation would be that a foreigner married to a Filipino citizen would hold title in the Filipino spouse’s name. The foreign spouse’s name cannot be on the Title but can be on the contract to buy the property. In the event of the death of the Filipino spouse, the foreign spouse is allowed a reasonable amount of time to dispose of the property and collect the proceeds or the property will pass to any Filipino heirs and/or relatives.

Can a Former Natural-Born Filipino Citizen own Private Land in the Philippines?

Any natural-born Philippine citizen who has lost their Philippine citizenship may still own private land in the Philippines (up to a maximum area of 5,000 square meters in the case of rural land). In the case of married couples, the total area that both couples are allowed to purchase should not exceed the maximum area mentioned above.

Can a Former Filipino Citizen, Balikbayan or OFW Buy and Register Properties Under Their Name?

Former natural-born Filipinos who are now naturalized citizens of another country can buy and register, under their own name, land in the Philippines (but with limitations in land area). However, those who avail of the Dual Citizenship Law in the Philippines can buy as much as any other Filipino citizen.

Under the Dual Citizenship Law of 2003 (RA 9225), former Filipinos who became naturalized citizens of foreign countries are deemed not to have lost their Philippine citizenship, thus enabling them to enjoy all the rights and privileges of a Filipino citizen regarding land ownership in the Philippines.

How to Gain Dual Citizenship in the Philippines

- If you are in the Philippines, file a Petition for Dual Citizenship and Issuance of Identification Certificate (pursuant to RA 9225) at the Bureau of Immigration (BI) and for the cancellation of your alien certificate of registration.

- Those who are not BI-registered and overseas should file the petition at the nearest embassy or consulate.

Can a Former Natural-Born Filipino Citizen own Private Land in the Philippines?

Any natural-born Philippine citizen who has lost their Philippine citizenship may still own private land in the Philippines (up to a maximum area of 5,000 square meters in the case of rural land). In the case of married couples, the total area that both couples are allowed to purchase should not exceed the maximum area mentioned above.

Requirements:

- Birth Certificate authenticated by the Philippine National Statistics Office (NSO)

- Accomplish and submit a Petition for Dual Citizenship and Issuance of Identification Certificate to a Philippine embassy, consulate or the Bureau of Immigration

- Pay a US$50.00 processing fee, schedule, and take an “Oath of Allegiance” before a consular officer

- The Bureau of Immigration (BI) in Manila receives the petition from the embassy or consular office. The BI issues and sends an Identification Certificate of Citizenship to the embassy or consular office.

If a former Filipino who is now a naturalized citizen of a foreign country does not want to avail of the Dual Citizen Law in the Philippines, he or she can still acquire land based on Batas Pambansa (BP) 185 and RA 8179, but limited to the following:

For Residential Use (BP 185 – enacted in March 1982):

- Up to 1,000 square meters of residential land

- Up to one (1) hectare of agricultural of farmland

For Business/Commercial Use (RA 8179 – otherwise known as the Foreign Investment Act of 1991):

- Up to 5,000 square meters of urban land

- Up to three (3) hectares of rural land

Real Estate Transaction Costs in the Philippines

Purchases from Individuals

- Capital Gains Tax – 6% of actual sale price. This is paid by the seller but in some cases, the buyer might be expected to be the one to pay. This percentage could differ if the property assessed is being used by a business or is a title owned by a corporation, in this case, the percentage is 7.5%.

- Document Stamp Tax – 1.5% of the actual sale price. This is paid by either the buyer or the seller upon agreement. Normally, however, it is the buyer who shoulders the cost.

- Transfer Tax – 0.5% of the actual sale price

- Registration Fee – 0.25% of the actual sale price

Purchases from Developers

- Capital Gains Tax – 10% of actual sale price. This value might be expressed as part of the sale price.

- Document Stamp Tax – 1.5% of the actual sale price

- Transfer Tax – 0.5% of the actual sale price

- Registration Fee – 0.25% of the actual sale price

In Philippine civil law, rescissible contracts are a subset of defective contracts under the Civil Code that are valid and binding until they are rescinded due to circumstances that render them legally vulnerable. Rescission is a remedy that seeks to restore the contracting parties to their original state (status quo ante) before the contract was entered into. These contracts are considered rescissible not because they are initially void or voidable but because they cause or threaten to cause damage to one of the parties or to a third person. The detailed regulations concerning rescissible contracts are outlined in Articles 1380 to 1389 of the Civil Code of the Philippines.

CHARACTERISTICS OF RESCISSIBLE CONTRACTS

- Validity: Rescissible contracts are valid and binding from the outset, meaning they produce legal effects and are enforceable until rescission is sought and granted.

- Ground for Rescission: The key reason for rescission is the presence of “lesion” or damage to one of the parties or to a third person, typically due to an inequitable result or bad faith. However, rescission is not applicable to contracts that are inherently void or voidable.

- Nature of the Remedy: Rescission is a subsidiary remedy, meaning it cannot be availed of if there are other legal remedies sufficient to address the injury or damage. It also means that rescission will only be granted if restitution to the status quo is feasible.

GROUNDS FOR RESCISSION (ARTICLE 1381)

The following contracts are rescissible under Article 1381 of the Civil Code:

- Contracts Entered into by Guardians: Contracts made by guardians in representation of their wards, if the wards suffer economic prejudice as a result, are rescissible. The law provides special protection for minors and incapacitated persons who are under guardianship, so any contract that prejudices them is subject to rescission.

- Contracts on Behalf of Absentees: Contracts executed by representatives of absent persons (e.g., those who are not physically present or are otherwise incapacitated) are rescissible if they cause prejudice to the absentee. This typically protects absent heirs, co-owners, or other individuals who are not physically present to protect their interests.

- Contracts to Defraud Creditors: When contracts are made with the intent to defraud creditors (often called “fraudulent conveyances” or “acts in fraud of creditors”), they are rescissible. This typically occurs when a debtor alienates property to evade fulfilling obligations to creditors.

- Contracts Relating to Litigious Things: Sales or assignments of items under litigation without notifying the parties involved in the lawsuit are rescissible. This rule aims to prevent contracts that could disrupt the proper administration of justice by transferring assets that are the subject of an ongoing legal dispute.

- Other Cases Expressly Stated by Law: Some other specific cases not enumerated in Article 1381 are also rescissible when expressly provided for by law.

PROCEDURE FOR RESCISSION

- Petition for Rescission: A party who wishes to rescind a contract must file an action for rescission in court. Rescission is not automatic; it must be judicially decreed through a formal judgment.

- Return of Benefits Received: The law requires that the parties return to each other what they have received under the contract. Rescission thus aims to restore both parties to their original positions. For instance, if the contract involved a sale, the buyer must return the item purchased, and the seller must return the payment made.

- Subsidiary Remedy: Rescission is only available as a last resort. If the aggrieved party has other remedies that can rectify the situation (such as damages), rescission will not be granted.

- Limitations Period: The right to file an action for rescission has a prescription period (statute of limitations) of four years. This period may differ depending on when the contract was entered into and the specific nature of the rescissible ground, such as whether the action involves fraud or other circumstances.

FFECTS OF RESCISSION

- Restoration of the Original Status (Status Quo Ante): When a court orders rescission, the objective is to return both parties to their original state as if the contract had not been made. This involves the mutual restitution of the property, money, or benefits received by each party.

- Protection of Bona Fide Third Parties: If a third party acquires rights in good faith from a party to a rescissible contract, their rights are generally protected. This is particularly important in property transactions, as innocent third-party purchasers are often shielded from the consequences of the rescission.

- Liability for Damages: If restitution cannot fully restore the injured party to the original condition, the party seeking rescission may be entitled to additional compensation or damages to cover the loss or injury suffered.

SPECIAL CONSIDERATIONS

- Partial Rescission: If the contract has been partly fulfilled and rescission affects only part of it, only that part may be rescinded. For example, if a divisible contract includes rescissible and non-rescissible obligations, the court may rescind only the part of the contract that causes harm or prejudice.

- Impossibility of Restitution: If restitution becomes impossible (e.g., the subject matter has been destroyed or fundamentally altered), rescission cannot be granted. In such cases, alternative remedies such as indemnity for damages may be awarded to the injured party.

- Requisites for Successful Rescission:

- Injury or Damage: There must be proof of injury or damage to justify rescission. The burden of proof rests with the party seeking rescission.

- Existence of a Rescissible Ground: The contract must fall under one of the categories of rescissible contracts specified in the Civil Code.

- Absence of Alternative Remedies: The injured party must show that rescission is necessary because no other adequate legal remedies are available.

LIMITATIONS ON RESCISSION (ARTICLE 1383)

The Civil Code emphasizes that rescission is a subsidiary remedy; hence, it may not be granted if other sufficient remedies exist to repair the injury or damage. Additionally, rescission does not cover all damages or inequalities. Minor discrepancies or unfair terms that do not reach the level of “lesion” or substantial harm are generally insufficient for rescission. For instance, a contract cannot be rescinded merely because one party finds the terms unfavorable or wishes to change their mind.

ALTERNATIVE REMEDIES

If a contract does not meet the criteria for rescission but still produces unfair or prejudicial outcomes, other legal remedies may be pursued. These include:

- Damages: Compensatory damages may be awarded if the injured party can demonstrate a loss directly caused by the contract’s performance.

- Reformation of Contract: If the contract does not reflect the true intent of the parties due to error, fraud, or accident, it may be reformed rather than rescinded to accurately represent the parties’ intentions.

- Reduction of Penalty Clauses: In cases where penalty clauses within a contract are excessive or disproportionate, the court has discretion to reduce them.

- Rescission vs. Annulment: It is important to distinguish rescission from annulment. Rescission presumes a valid contract that can be rescinded due to injury, whereas annulment applies to contracts that are voidable due to lack of consent, mistake, or fraud.

For anyone renting or planning to rent a property in the Philippines, understanding the Rent Control Act is crucial. This law aims to protect tenants from unreasonable rent increases while ensuring landlords can still fairly profit from their properties. Let’s break down the key aspects of this act to help both tenants and landlords navigate their rights and responsibilities.

The law primarily covers:

– Residential units with a monthly rent of up to ₱10,000 in Metro Manila.

– Units with a monthly rent of up to ₱5,000 in other cities and municipalities.

Key Provisions

1. Limit on Rent Increases

2. Protection Against Eviction

-Non-payment of rent for three consecutive months.

-Subleasing without the landlord’s consent.

– The landlord needing the property for personal use or renovations.

3. Advance Payments and Deposits

– Landlords are allowed to collect up to one-month advance rent and two months’ deposit.

– Deposits must be returned to the tenant upon moving out, minus any deductions for damages.

4. Rental Contracts Both tenants and landlords are encouraged to have a written rental agreement specifying the terms and conditions of the lease, including rent, duration, and responsibilities.

Who Benefits from the Rent Control Act?

The act primarily benefits low- to middle-income families, students, and employees who rent affordable housing. It ensures they are not priced out of their homes due to sudden, excessive rent increases.

What the Rent Control Act Doesn’t Cover

The Rent Control Act does not apply to:

– Commercial properties.

– Residential units rented out for over ₱10,000 per month in Metro Manila and ₱5,000 per month in other areas.

– New leases not covered by existing agreements.

Recent Updates

While RA 9653 officially expired, the Philippine government often extends similar provisions to address housing affordability. As of today, tenants and landlords should stay updated with the latest housing and rental policies implemented by the Housing and Land Use Regulatory Board (HLURB) or other government bodies.

Tips for Tenants

– Always sign a written agreement and understand its terms before moving in.

– Keep records of your payments and communications with your landlord.

– Report any violations of the Rent Control Act to local housing authorities or barangay offices.

Tips for Landlords

– Familiarize yourself with the Rent Control Act to avoid legal disputes.

– Clearly communicate rental terms and increases with tenants in writing.

– Maintain the property to ensure tenants receive value for their rent.

Final Thoughts

The Rent Control Act is a critical safeguard for renters and a guide for landlords in managing rental properties. Whether you’re a tenant or landlord, understanding this law can foster a fair and harmonious rental relationship.

Stay informed about changes to rental policies and consult legal or housing experts for specific concerns. After all, a well-informed rental community benefits everyone.

Condo vs. House: Which is the Better Investment in the Philippines?

1.) Cost and Affordability

✅ Condo

• Generally more affordable than houses, especially in urban areas.

• Lower initial cash outlay and down payment.

• Comes with monthly condo dues for maintenance and amenities.

✅ House and Lot

• Higher upfront cost but offers full ownership of land.

• Maintenance costs are shouldered by the owner.

• Long-term appreciation potential due to land value.

2.) Location and Accessibility

✅ Condo

• Found in prime locations near business districts, malls, and schools.

• Ideal for professionals, students, and investors targeting rental income.

• High demand in Metro Manila, Cebu, and Davao.

✅ House and Lot

• Typically located in suburban or provincial areas.

• More peaceful environment, ideal for families.

• Can require longer travel time to city centers.

3.) Rental Income Potential

✅ Condo

• Easier to rent out due to location and amenities.

• Short-term rental options (Airbnb) can yield higher returns.

• Smaller units (studio, 1BR) have higher rental demand.

✅ House and Lot

• Better for long-term rentals, especially in family-friendly communities.

• Can accommodate multiple tenants if converted into a boarding house.

• More stable rental market compared to short-term rentals.

4.) Appreciation and Resale Value

✅ Condo

• Slower appreciation compared to land.

• Depreciation over time, especially for older buildings.

• Can be harder to resell due to market saturation.

✅ House and Lot

• Land value appreciates over time, making it a stronger long-term investment.

•More flexibility to renovate, expand, or rebuild for better resale value.

• Lower depreciation risk compared to condos.

5.) Ownership and Restrictions

✅ Condo

• Ownership is limited to the unit; the land belongs to the developer.

• Monthly condo dues and association rules apply.

• Leasehold terms apply (up to 50 years for foreign investors).

✅ House and Lot

• Full ownership of both land and structure.

• No association fees unless in a subdivision.

• More freedom to customize and modify the property.

6.) Maintenance and Expenses

✅ Condo

• Requires minimal upkeep since the condo management handles maintenance.

• Monthly association dues for amenities and security.

• Higher costs for repairs and renovations due to strict rules.

✅ House and Lot

• Owner is responsible for all repairs and maintenance.

• No mandatory monthly fees unless in a gated community.

• More freedom to renovate, expand, or rebuild.

A simple, complete guide to Republic Act No. 6552 (Realty Installment Buyer Protection Act)

Buying a home or condominium through installment is one of the most common ways Filipinos acquire real estate. But what happens if a buyer can no longer continue payments? Do they automatically lose everything?

This is where the Maceda Law comes in.

Passed as Republic Act No. 6552, the Maceda Law—also known as the Realty Installment Buyer Protection Act—was created to protect buyers of real estate sold on installment. It outlines the rights of buyers, grace periods, refunds, and the correct legal process when a buyer defaults.

If you are purchasing a house, lot, townhouse, or condominium through installment (except rent-to-own or mortgage loans), this law applies to you.

Here’s a clear, simple breakdown of what the Maceda Law provides.

1. What Is the Maceda Law?

Republic Act 6552 (Maceda Law) protects buyers of real property sold on installment, specifically:

- House and lot

- Lots

- Townhouses

- Condominiums

- Any real estate (except industrial lots, commercial buildings, and agricultural land)

It applies when the sale is directly from the developer or seller and paid through installments—not through bank loans, Pag-IBIG financing, or mortgage contracts.

2. Who Is Protected Under the Maceda Law?

You are protected if:

- You bought real property through installment

- You have made at least two years of installment payments

- The property is for residential use

The law is buyer-friendly and ensures that if you can no longer pay, you still get certain rights.

3. If You Have Paid at Least 2 Years of Installments:

You Are Entitled to a Refund

Under Section 3 of RA 6552, if a buyer has paid at least 2 years of installments, the developer must grant:

1. A 60-day grace period

You are given a minimum of 60 days to settle overdue payments without losing your rights.

2. A refund of 50% of total payments made

If the contract is canceled after the grace period, you are entitled to a refund:

- 50% of total payments made, and

- After 5 years of installments, an additional 5% per year, capped at 90% total refund

This refund must be paid before the developer can formally cancel the contract.

This protects buyers from losing everything they paid.

4. If You Have Paid Less Than 2 Years of Installments: You Still Get Rights

Even if you paid less than 2 years, RA 6552 still grants:

A 60-day grace period

You cannot be evicted or canceled immediately.

You must first be given written notice, and then the 60-day grace period starts.

If you fail to pay within 60 days, only then can the seller cancel the contract through the proper legal process.

No refund is required for buyers who paid less than 2 years.

5. Contract Cancellation Must Follow Legal Procedure

A developer or seller cannot just lock you out, change the door, cancel verbally, or take back the property without due process.

Under the Maceda Law:

✔ The cancellation must be in writing

✔ Delivered through a notarial act of cancellation

✔ Refund (if applicable) must be issued before cancellation

✔ Only after these steps can the seller resell the property

6. You Can Sell or Assign Your Rights Before Cancellation

RA 6552 allows buyers to:

- Sell their rights to another buyer

- Assign the property

- Transfer the contract

- Change ownership

…before cancellation or default.

This gives flexibility to buyers who want to avoid losing their investment.

7. Why the Maceda Law Exists

The law was created to:

✔ Protect hardworking Filipinos buying homes through installment

✔ Prevent developers from abusing buyers

✔ Ensure fairness in contract cancellation

✔ Provide reasonable grace periods

✔ Allow refunds for long-term payers

It is considered one of the strongest buyer-protection laws in Philippine real estate.

8. Maceda Law vs. Rent-to-Own vs. Mortgage Financing

The Maceda Law applies only to installment sales.

It does not apply to:

- Bank-financed home loans

- Pag-IBIG housing loans

- In-house financing already converted to mortgage

- Rent-to-own lease agreements

- Commercial or industrial property

Each of these has different rules and protections.

9. Common Misconceptions — Clarified

❌ “If I miss one payment, the developer can evict me.”

✔ False. You have a legal 60-day grace period.

❌ “I lose everything if I can’t continue payments.”

✔ False. If you’ve paid at least 2 years, you get a refund.

❌ “Cancellation can be verbal or through text.”

✔ False. Cancellation must be through a notarial act.

❌ “The developer can refund anytime.”

✔ False. Refund must be paid before cancellation.

10. Why Understanding the Maceda Law Helps Buyers and Investors

Knowing your rights allows you to:

- Protect your investment

- Avoid abusive practices

- Make informed decisions

- Plan financing more clearly

- Safeguard your hard-earned money

- Negotiate better with developers

Final Thoughts: The Maceda Law Protects Your Real Estate Investment

Buying real estate is one of the biggest financial decisions you will ever make.

The Maceda Law (RA 6552) ensures that:

- You get protection

- Your payments are valued

- You are treated fairly

- Your rights are respected

Whether you are buying a pre-selling condo, a house and lot, or a subdivision property, knowing this law empowers you as a buyer.